Doing It with Charlie

How Charlie Munger’s psychology of misjudgment explains the slow ruin of a blue chip once thought invincible.

I wrote this piece to openly examine a past decision that simply did not meet its promise. Figuring out the “why” is crucial. While I have privately dissected this mistake before, I think publishing this analysis holds me accountable and forces a greater discipline in my thinking. I also hope it serves as a real-world case study for readers on how investment processes can fail and be improved. This is 100% self-critique and not to pass judgment on the company or its management. I cannot promise I will never make a mistake again, but I can certainly commit to using an upgraded process going forward.

If there is one constant in investing, it is that the pendulum never stops swinging. It oscillates repeatedly between euphoria and despair, never pausing for long in the middle.

Right now, it feels like Singapore’s market is back on the upswing. There is talk of a “boom.” Fresh funds are flowing in to reinvigorate the local exchange. The Monetary Authority of Singapore has launched a S$5 billion program to develop the equity market. It is an appealing narrative that paints a picture of a well-managed and well-capitalized market poised for growth.

But experience warns that when the story sounds this good, it is time to remember the last time it did not. The best antidote to exuberance is a painful memory, bar none.

My personal reckoning came from what I once thought was the safest of bets. My investment in Singapore Press Holdings (SPH). For decades, SPH was the quintessential blue chip. A fixture of the Straits Times Index (STI, main barometer for the performance of the Singapore stock market), seemingly unassailable, government-linked, and reliably dividend-paying. It dominated Singapore’s news printing industry, holding a state sanctioned monopoly that made it as much an institution as a company. To many, it appeared immune to disruption or decline. In the eyes of investors, it was not just a business but part of the country’s foundation. It looked like a company that could not fail.

And yet it did. Its decline and eventual delisting wiped out millions in shareholder value. More importantly, it reminded me that most investment mistakes are not so much analytical as they are psychological. We fall in love with stories, reputations, and symbols of safety. Often forgetting that they are not invulnerable to market truths.

This post is not so much about revisiting the past for its own sake as it is about examining how I got it wrong, and how the same patterns of thought can repeat themselves in markets that look healthy today. It is also an attempt to reflect on the cognitive biases through the lens of psychological misjudgments compiled by Charlie Munger whose framework I will cite unreservedly throughout. Back then, I did not appreciate the deep influence of psychology on decision-making as much as I should have. Today, it would feel strange to conduct a post-mortem on an investment mistake without acknowledging that crucial human element.

The SPH story, painful as it is, offers a clear warning. Markets have no tolerance for stasis and complacency. As sterling as blue chips are, they can also fail as investments and investors should not mistake comfort for safety and permanence for durability.

More importantly, this is not just about one company’s decline. It is a reminder that even in a well-regulated, prosperous market, risk often hides in plain sight. Policy support can revive activity, but it is not substitute for good management or sound fundamentals. The phrase “buyer beware” remains timeless. Before we embrace the next “safe” story, it is always worth remembering that even the strongest can fall and often from within.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this, consider subscribing to get new posts delivered to your inbox. Your support means a lot and helps this publication grow.

The Fortress Illusion

To understand how an investment fails, we must first understand why it seemed so safe in the first place.

Source: SPH HQ

SPH was, by design, a fortress. Formed in 1984 through a government-led merger of its main newspaper rivals, it was granted a near-monopoly under the Newspaper and Printing Presses Act. From that moment on, it became the gatekeeper of Singapore’s news-printing industry, a company that did not just report the nation’s stories but became part of it.

With flagship publications like The Straits Times and Lianhe Zaobao (Chinese Equivalent) that are the country’s de facto newspapers, paying steady dividends, and a prominent place in STI, SPH appeared every bit the model blue chip. Over time, it even diversified into property, most notably the Paragon shopping mall, reinforcing the impression of stability and prudence.

That was the stronghold of stability I believed I was buying into in 2014, when I first invested at around S$3.75 with ~5+% dividend yield. In hindsight, my reasoning was less analysis and more psychology. I mistook reputation for resilience. I equated “blue chip,” “government-linked,” and “trusted brand” with “invincible.” Charlie Munger would call that the Influence-from-Mere-Association Tendency, our habit of confusing connection for causation, assuming that anything linked to something good

“A final serious clump of bad thinking caused by mere association lies in the common use of classification stereotypes.” – Charlie Munger

I was also comforted by the company’s popularity. SPH was a core index holding, owned by institutions and retirees alike. If everyone around me thought it was safe, it had to be safe. Munger identified that as the Social-Proof Tendency, an apt label for the human urge to seek safety in numbers.

“The otherwise complex behavior of man is much simplified when he automatically thinks and does what he observes to be thought and done around him.” – Charlie Munger

What I failed to do was to think more critically. A more astute investor would have asked “What could make it fail?” instead of being focused on “What makes SPH so secure?”. The warning signs were there even then. Profits and revenue were already deteriorating. I saw those numbers but rationalized them away, convincing myself that property income would smooth the cycle and that the decline was temporary.

I saw the fortress, but ignored the cracks spreading through its foundation.

Denial in the Face of Disruption

While predicting the future is impossible, we should be able to assess the dominant forces shaping the present. The internet did not arrive overnight. It unfolded in plain sight, reshaping how businesses connected with customers and how value was created. The notion that it would disrupt how people consumed news was hardly radical. SPH’s undoing was not failing to recognize that change but denying that it was already happening. The company’s century-old, monopolistic model was already being overtaken, but admitting that truth would have meant questioning everything that had once worked. Munger diagnosed this as “Simple, Pain-Avoiding Psychological Denial.”

“The reality is too painful to bear, so one distorts the facts until they become bearable.” – Charlie Munger

The internet systematically dismantled SPH’s profitable ecosystem.

First, the company’s most lucrative segment, the high-margin classifieds business, was utterly dismantled by specialized digital-only entrants in areas like property, recruitment, and motoring.

Second, the global tech giants, the likes of Google and Facebook, had already created an advertising duopoly built on speed, precision and scale that print could not match by then.

In hindsight, the first clear data point confirming the terminal illness may even have actually appeared in fiscal year 2012, when property revenue rose while the core Newspaper & Magazine segment’s revenue dipped. The slow decay had begun.

It seemed like management’s response was to cling to their established identity. The human brain is reluctant to change, and SPH’s corporate brain looked no different back then. Perhaps they were fundamentally a print company, and their organizational memory prevented them from seeing past this identity. In effect, every critical operational system was hardwired for a dying business model.

Instead of executing the wholesale fundamental reinvention the market demanded, they made tactical, ancillary changes. They launched websites and apps that were merely new containers, designed explicitly to preserve their legacy print advertising structures rather than build scalable new digital revenue. This was perhaps a costly act of corporate self-deception, digitizing the form while keeping the substance unchanged and protecting the comfortable, familiar path instead of mastering the unfamiliar future. What passed for transformation was just optimization of a model already in decline. The human brain’s inertia to change is a trait Munger labels “Inconsistency-Avoidance Tendency.”

“Also tending to be maintained in place by the anti-change tendency of the brain are one’s previous conclusions, human loyalties, reputational identity, commitments, accepted role in a civilization, etc.“ – Charlie Munger

A better response would have been to follow Darwin’s example as Munger explicated in his discourse on misjudgements. Ruthlessly seek out evidence that disproves your most cherished beliefs and adapt or die. Instead of adapting to what is underway, management remained cloistered in their ivory tower, making decisions based only on past successes. A curious case of using the rear-view mirror to drive through a landscape that had completely changed.

Comfort over Change

A company’s capital allocation decisions reveal more than its numbers. They also expose its beliefs. Faced with the slow collapse of its media business, SPH’s leadership chose the path of least resistance. Instead of confronting the structural problem, they used the cash flows from a dying franchise to buy stability elsewhere. They built a lifeboat out of property. It was, in hindsight, a failure of imagination more than of execution.

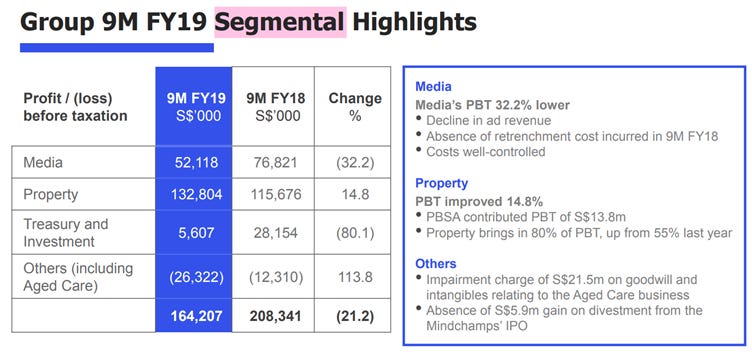

Property was familiar and comforting. Digital transformation, by contrast, was messy and uncertain. When confronted with disruption, they did what felt natural, they reached for what they already understood. They began an aggressive diversification into student housing in the UK and Germany, and aged-care assets in Singapore and Japan. By 2019, property contributed more than 70% of profit before tax. SPH had become, in substance, a property company still carrying a media division it no longer believed in.

Source: The Cash Cow is Property, not the Press

Charlie Munger referenced the man-with-a-hammer syndrome in his speech on The Psychology of Human Misjudgment repeatedly. To someone who knows only one tool, every problem looks like a nail. SPH’s pivot was exactly that. They represented a retreat into the familiar instead of renewal of purpose.

A leadership team that truly believed in journalism’s future would have invested to defend and reinvent it. In the end, SPH invested not in what was coming, but in what it already understood.

The Psychology of Holding On

My first mistake in 2014 was analytical. The second, and far more costly, was psychological. As the evidence mounted against my thesis, I held on. Then I made the one move that turns a mistake into a disaster: I doubled down. I told myself that a monopoly this entrenched could not possibly fail. It was, as Charlie Munger would say, a “Lollapalooza effect”. A perfect storm of biases working together to produce an irrational outcome.

“It accounts for the extreme result in the Milgram experiment and the extreme success of some cults that have stumbled through practice evolution into bringing pressure from many psychological tendencies to bear at the same time on conversion targets. “ – Charlie Munger

Having built my case around the “unassailable fortress” narrative, I found it almost impossible to believe that a company with such monopolistic power could allow itself to succumb to external market forces. Letting go would have meant admitting that even Porter’s Five Forces offer no protection when an industry is structurally disrupted. A reminder that monopolies too, are not immortal. It also would have meant confronting an error of commission, in Buffett’s terms, something investors, myself included, are rarely good at.

I did what comes most naturally when conviction is blighted by discomfort. I searched for evidence that proved me right. I focused on the growth of the property segment and mentally downplayed the steady decline in media. It was Confirmation Bias at work, the tendency to defend the ego long after the facts have changed.

The second was Anchoring. I could not detach from my entry price of S$3.75. Every drop below that number looked like opportunity rather than evidence. I was not evaluating value anymore, I was defending a reference point.

The third, and most powerful, was what Munger called “Deprival-Superreaction”. The pain of realizing a loss outweighed the discomfort of staying wrong.

“He will often compare what is near instead of what really matters. For instance, a man with $10 million in his brokerage account will often be extremely irritated by the accidental loss of $100 out of the $300 in his wallet.” – Charlie Munger

I told myself that things would turn, that the dividend cuts from 21 cents in 2014 to 13 cents by 2018, will be temporary. They were not. Each one was a warning, and I rationalized every single one away.

Instead of searching and waiting for a catalyst would make the stock go up, the real task was to ask what the blueprint for permanent capital loss might look like. The steady erosion of the core business was there in plain sight. But a cluster of biases, acting in concert, made it impossible to see what was right in front of me.

What I Failed to See

The digital disruption that hit SPH was not unique, it was part of a global, secular shift. My real mistake was not just in misreading the company. It was also a failure to read the world around it. I should have been inquiring how were others in the same storm adjusting their sails, and why was SPH sailing in the opposite direction?

Now in retrospect, the actions of its global peers offered more than clues. They were open lessons, visible to anyone willing to look. Each one revealed, in its own way, what conviction and reinvention looked like in practice.

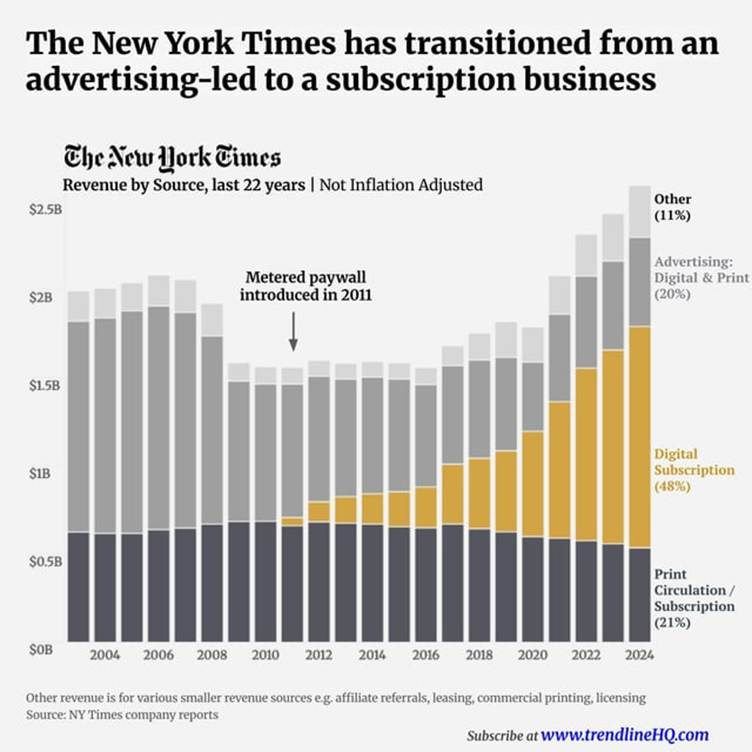

The New York Times chose to double down on its core mission. It built a durable subscription model around the idea that high-quality journalism was worth paying for. Management invested heavily in digital engagement, from a seamless paywall to adjacent product categories like cooking and games. It was a clear statement of belief in the value of their craft. SPH, by contrast, tried to optimize a shrinking ad model and sought refuge in property. That choice said less about diversification and more about resignation.

The Guardian took a different but equally courageous route. It bet on community by inviting readers to support its journalism voluntarily, treating it as a public good. The result was loyalty, independence, and a buffer from the volatility of ad markets. SPH, by contrast, failed to articulate a bold digital strategy. Its attempts at adaptation amounted to insufficient measures, including soft paywalls and minor platform redesigns, which failed to move the organization away from its deep-seated reliance on print revenue.

The Nordic publisher Schibsted offered the hardest lesson of all. Cannibalize yourself before someone else does. Seeing its lucrative classifieds moving online, it built digital marketplaces that replaced its own print profits in early 2000s before competitors could. SPH had a multi-year head start to observe the cannibalization strategy needed to protect its highest-margin business in classifieds. The failure to react decisively during the 2000s is why local startups later like PropertyGuru obliterated this revenue.

The contrast could not have been clearer. Where others reinvented, SPH defended. Those differences should have been a blaring signal to reassess, where the evidence all pointed one way, yet I refused to move. The failure was not just in picking the wrong stock, it was also in ignoring the lessons freely available.

The Reckoning

The height of success is often merely the prelude to the next self-inflicted reversal. The final years of SPH as a listed company proved that truth painfully well. What began as gradual complacency turned, over time, into drift and when the reckoning came, it was swift and unforgiving.

The first blow was symbolic, but it mattered deeply. In June 2020, SPH was removed from the STI, the very benchmark of Singapore’s corporate elite. For a company long seen as a pillar of the local market, the removal was more than a technical adjustment. SPH was no longer a blue chip.

The numbers soon confirmed the symbolism. In October that same year, SPH reported its first full-year net loss. Management cited the pandemic and the collapse in advertising revenue, and there is no doubt that COVID-19 dealt a heavy blow. But the truth is, the tree was already rotting before the storm arrived. A healthy business would have bent but this one broke.

The pressure reached its peak in May 2021, during the now-infamous press conference announcing the plan to spin off the media business. The moment is remembered for one word “umbrage.” The defensive reaction said less about temperament than about strain. As Charlie Munger described in his Stress-Influence Tendency, people under duress often act in ways that amplify the very problem they face.

“Most people know very little about non-depressive mental breakdowns influenced by heavy stress.” – Charlie Munger

A calmer acknowledgment of the question might have reflected leadership under pressure. Instead, it revealed a company that had lost touch with its own mission.

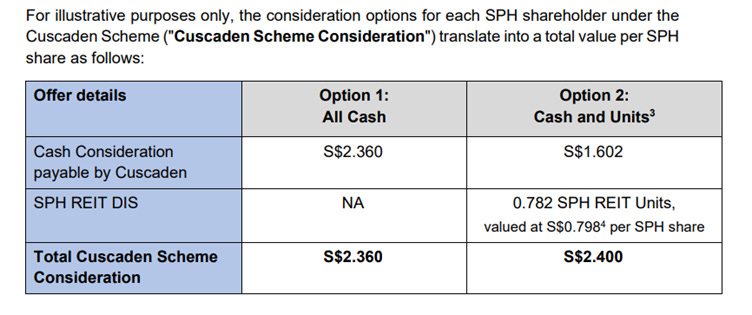

The spin-off itself was the final admission that the game was over. The once-prized media arm was transferred to a not-for-profit entity, SPH Media Trust, supported by an S$80 million cash injection and additional units in SPH REIT. What remained of SPH, the property holdings and residual businesses, became the object of a bidding war between Keppel Corporation and a consortium led by Cuscaden Peak. Cuscaden eventually prevailed. On May 13, 2022, SPH was delisted and renamed Cuscaden Peak Investments. Shareholders were given the option of taking an All-Cash consideration of $2.36 or cash and pro-rata SPH REIT units valued at ~$2.40.

I chose the latter option and accepted a ~30% capital loss. This figure did not account for the forgone time value of money over the years, which would have dramatically worsened the real return. This failure was the costly consequence of adhering to biases that kept me tethered to a failing business model. The terms I accepted were not so much a payout as it is a post-mortem settlement on a failed thesis.

From market darling to delisted subsidiary, the journey took less than a decade. The decline was not sudden but the cumulative result of comfort and denial, a slow erosion that only looked inevitable in hindsight.

Reflections

My mistake in investing in SPH was fundamentally a failure of second-level thinking, driven by a Lollapalooza effect of psychological misjudgements. I fell for a simple, comforting narrative and ignored the essential discipline of imagining what might go wrong. Underestimating the relentless strength of a paradigm shift and overestimating the ability of an entrenched, successful incumbent to change its ways. The fundamental truth uncovered by the SPH saga is plainly visible and deeply consequential.

No moat is permanent, and the past is a poor guide to the future when an industry’s fundamental economics are being rewritten.

The belief that a blue chip’s dominance is insurmountable is not an investment thesis, more like a dangerous bias.

This brings me back to the present. The prevailing optimism surrounding a new market boom, fueled by government initiatives and institutional capital, feels uncomfortably similar to the “unassailable fortress” narrative that once surrounded SPH. The idea that institutional buying alone signals strength is a false correlation. The flow of capital is irrelevant if the underlying value is not there. Real strength is built not on capital flows, but on the quality, profitability, and corporate stewardship of the market’s constituents over decades.

Still, the painful experience of SPH must not lead to a new form of error. Just as we must avoid herd optimism, we must also guard against anchoring ourselves to past losses. The memory of ruin should not paralyze us. We cannot let a past failure permanently blind us to genuine opportunity.

The investor’s job is not to predict the future based on the past, but to review each new development strictly on its own merit. While we must be vigilant against market euphoria, we must not be perpetually anchored to the fear of the last cycle. If genuine value surfaces, we must retain the conviction required to seize it.

To test the perceived safety of any blue chip, I now measure its vulnerability against the painful blueprint for ruin that SPH laid bare. Its downfall was not a single event but a long, slow decay born of complacency, a failure of imagination and stewardship that chose comfort over change. While SPH is not a reflection of the Singapore market, it provides a reminder to investors everywhere that even the strongest franchises can fade if they stop adapting. The market’s history in every country is filled with once “unassailable” names.

I am convinced that the belief that any company is invincible remains one of the costliest illusions an investor can hold.

This post-mortem was, in part, inspired by a post that shared regarding another fund manager’s candid reflection on a failed investment within his own investor letter. The lesson that lingered was not about the loss itself, but the degree of honesty that followed it. In this craft, self-awareness is far more valuable than foresight and prediction. If readers find nothing else of value from my post, they would do well at least to read that post and emulate the candour.

A sharp excavation. You cleverly identify the enemy not in the market, but in the mind’s flawed assumptions. By mapping Munger’s models of misjudgment onto the SPH ruin, you deliver a disciplined self-critique. This is exactly the sort of work required to derive lasting insight from a costly experience.

This is rare... a post that doesn’t just analyze failure but exposes the quiet mechanics behind it. You captured how comfort turns into blindness, how narrative defends itself against reality.

The SPH story reads like a study in systemic inertia. Identity protecting itself until it breaks. What gives this piece weight is the honesty. Reflection as discipline, not confession. That’s what real coherence looks like in finance and beyond. I feel very connected with you. I will restake it with a comment!